Some diseases can be diagnosed by identifying physical changes in tissue, such as the hardening of

arteries during heart disease. Diseased cells often exhibit different mechanical characteristics, or

mechanotypes, than normal cells. Efficient tools for measuring mechanotypes could allow doctors to

diagnose diseases at an early stage, predict whether a tumor might metastasize, and identify effective

drugs and genes linked to certain diseases.

In a promising development for cancer screening and treatment, groundbreaking research published in

Nature Communications by a team of U of M researchers from the Medical School and College of

Biological Sciences has led to a new laboratory test to measure cell mechanotypes quickly and easily.

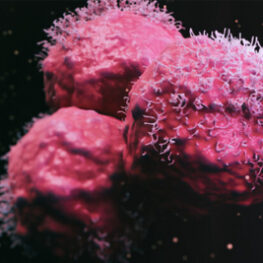

Cells constantly move through the body and interact with other cells. Cancer cells may move more

aggressively than other cells, in some cases pulling on the tissue around them. Metastatic cancer cells

sometimes exhibit less pull than others. In the past 25 years, scientists have evaluated these pulling forces with tools like microscopy, which are effective but difficult to use and time-intensive, resulting in

bottlenecks for cancer research.

The research team wanted to develop a more rapid method of evaluation. They discovered:

By using tension gauge tethers (TGTs), or small bits of double-stranded DNA that break apart when cells

attach and pull on them, they were able to evaluate how different types of cancerous cells differentially

break apart the DNA.

By attaching fluorophores to TGTs that get delivered into the cells interacting with the TGTs, they can

evaluate thousands of cells quickly without microscopy and also sort cells according to their

mechanotype.

The RAD-TGT (“Rupture and Deliver Tension Gauge Tethers”) tool can differentiate between

mechanotypes among mixed populations of cells, opening up the possibility of identifying genes linked to diseases.

“We can measure thousands of cells’ fluorescence in minutes using an instrument called a flow cytometer and then isolate the cells by their distinct mechanotype,” said author Wendy Gordon, associate professor of biochemistry, molecular biology and biophysics. “We are now working to use this assay to study the mechanotypes of several different cancers.”

The RAD-TGT tool also helps evaluate problematic cells at different states. For example, in a

metastasizing cancer, the cancer cells may become squishy to squeeze through blood vessels and enter

other parts of the body. In that case, a drug that makes cells more firm could be beneficial. This tool will

help researchers evaluate the varying states of the disease and cell progression.

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health.